I have watched nearly every one of the documentaries that Ken Burns has produced. Of his collection, “The Vietnam War” (2017) has made the deepest impression on me; I have watched its ten episodes (a total of 16 viewing hours) three times. The series features interviews with 79 witnesses, including many Americans who fought in the war or opposed it as Anti-war protesters, as well as Vietnamese combatants and civilians from both the North and the South.

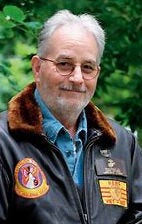

Of all these witnesses, two impressed me the most: John Musgrave and Tim O’Brien (whom I will write about in a future post).

John Musgrave was seventeen in 1966 when he and his best friend enlisted in the Marine Corps in Independence, Missouri. He joined because his father and most of the men he’d known and admired had served in World War II or Korea. Musgrave said, “There was a war on, and I wanted a piece of it.”

He was shipped out to Vietnam as 1966 came to a close. “To say that I went over there uninformed would be an understatement. I didn’t know anything about the Vietnamese, and I didn’t care.”

Musgrave was initially assigned to an MP battalion at Danang. He wanted more. “I joined the Marine Corps to be in the varsity, and I felt that I wasn’t varsity unless I was up north fighting the NVA. I have never regretted the decision. I thought then, if I lived to be sixty-three years old, I didn’t want to look in the mirror some morning and have a guy looking back at me that hadn’t done everything for what he believed, who let somebody else do the hard part.”

When a recruiter turned up asking for volunteers to replace men killed and wounded further north, he stepped forward. He was sent to Con Thien, located near the Vietnamese Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) about two miles from North Vietnam. U.S. Marines who endured life there came to call it “the Bull’s-Eye” and “the Graveyard.” The DMZ became known as the “Dead Marine Zone.”

“We were the fish,” said Musgrave. “They had the shotguns; they stuck them in the barrel (the small area of Con Thien) and blasted away, knowing they were going to hit something with every shot.

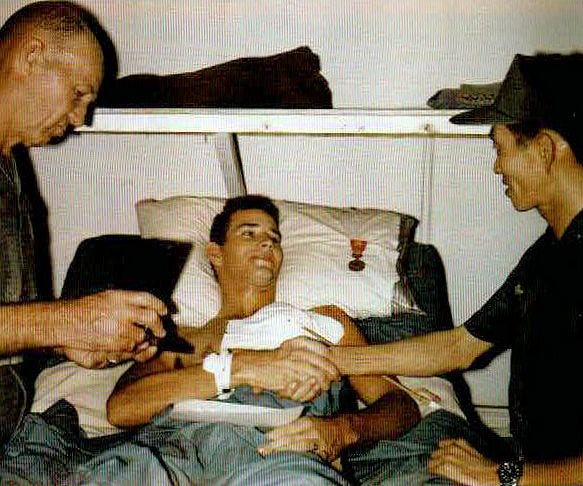

Before dawn on November 7, 1967, eleven months and seventeen days into Musgrave’s tour of duty, two companies from his outfit were sent into the countryside to conduct a sweep. John was one of the first of many to be shot. He had a hole through his chest big enough to stick your fist through. He recalled, “I’m dying, and I know it. I heard this horrible screaming going on, and I tried to figure out who it was…and then I realized it was me.”

Musgrave was helicoptered to a medical Quonset hut where doctors told him they couldn’t help him and called for a chaplain. But another surgeon passed by and said, ’Why isn’t anyone helping this man?” Musgrave had wondered the same.

Wounded in the jaw and shoulder, his ribs shattered, lung pierced, nerves cut, he spent seventeen months in Navy hospitals and returned home to enroll in college in Kansas. Musgrave was so hurt by the way the U.S. was treating returning soldiers (“Baby killers!”) that he volunteered to return to Vietnam, but he was turned down because of his injuries.

He gradually came to feel as if he were being torn in two and was still haunted by the memory of those Marines who had died while he had lived. He said, “I was dating my .45 in those years. Coming home at night after drinking and pressing it up against my temple or putting it under my chin, wondering if this was going to be the night I was going to have the guts to do it.”

Richard Nixon’s troop withdrawals finally turned Musgrave against the war. “If it ain’t worth winning,” he thought to himself, “it ain’t worth dying for.”

Musgrave would join some 2,300 war veterans, members of a five-year-old organization called Vietnam Veterans Against the War (VVAW). They were coming to Washington D.C. on April 23, 1971, planning to camp on the Mall between the Lincoln and Washington monuments for a week of lobbying and demonstration. Musgrave was among the marchers. He had slowly come to realize that “I wasn’t helping anybody by keeping my mouth shut.” His loyalty to the Marine Corps never wavered even as his faith in its mission in Vietnam dwindled.

One of the most dramatic moments of the march came when decorated Vietnam veterans, one by one (Musgrave included), stepped up to a microphone to identify themselves and speak out against the war and then hurled their medals onto the Capitol steps—Silver Stars, Purple Hearts, Bronze, Stars, Distinguished Flying Crosses.

Musgrave raised money for the Vietnam Veterans Memorial at the University of Kansas, and he served on the committee that helped see its completion. The Memorial opened in1982. He remembers his first visit: “As I was walking toward it from the reflecting pool, there were so many names on those walls. And all of a sudden, my throat swelled up and I thought, ‘I can’t do this right now.’ And I collapsed. I was on my knees, sobbing. I couldn’t stop. I couldn’t get my breath. And I was so grateful to God that the memorial was there. I thought, it is going to save lives, this is going to save lives.”

Note: I extracted the above information about John from The Vietnam War: An Intimate History by Geoffrey C. Ward and Ken Burns.

AN EXCHANGE OF LETTERS

After my second viewing of “The Vietnam War,” I was so moved by Musgrave’s interviews that I wrote the following letter to him:

January 8, 2018

Dear John Musgrave,

I just finished my second watch of all episodes of Ken Burns’ The Vietnam War. I am a huge Burns fan and have viewed nearly every one of his masterpieces, but I find it hard to put into words the impact that The Vietnam War had on me. I learned so much about the United States, South Vietnam, and North Vietnam that I had not known before. I gained even more appreciation than I previously had for the Americans who served and for the Vietnamese—soldiers and civilians—as well.

Of all that was said and shown, your voice and your stories resonated most powerfully with me. I felt compelled to write to tell you so, to thank you for your service, and to commend you for agreeing to be part of the documentary. Like you, I was born in the Midwest (Clear Lake, Iowa) in 1948. Like your father, my father served in the military—he was in both WW II (artillery in Okinawa) and later in Korea. My grandfather served in WW I, being drafted off his Iowa farm to serve in Europe as that war wound down. Unlike you, I didn’t serve in Vietnam.

When I attended Iowa State in 1966, I joined ROTC my freshman year, not because I felt pressure from Dad to do so, but partly to help repay him for the sacrifices he had made. I did fine in ROTC, but the military way of life just wasn’t for me. As my second year of ROTC ended, I needed to decide whether to proceed and commit to multiple years in the Army following graduation or discontinue ROTC and take my chances with the draft. I’ll always remember Dad—my hero, best friend—telling me, “Mike, I’m not certain that this war is one you need to be fighting. If you want to drop ROTC, I’m fine with that. Don’t continue just for my sake.”

With Dad’s approval, I ended ROTC after my sophomore year. In the draft lottery my senior year, my number was 289. I graduated in the spring of 1970 and began a fruitful career at IBM in Rochester, Minnesota, shortly after and was never called to serve.

As I watched The Vietnam War, I thought were it not for my high lottery number I could have been in your shoes, or in those of some of the others interviewed, or one of the soldiers being stuffed into a body bag. How unfair life is for so many. Most are simply pawns in games they’d rather not play.

I believe my dad spent time in a military psychiatric ward in either WW II or Korea. Sadly, he suffered multiple bouts of depression that required hospitalizations and Electroshock Therapy beginning in 1969 and continuing until his death in 2016. He enjoyed many good years between the dark days and never uttered a word of complaint.

In one of your interviews, you commented on being a “dog’s bark at the front door” away from committing suicide. I’m not sure how close Dad got, and I’m not sure I want to know, but I gained from my experiences with him a tremendous respect for mental illness, PTSS, or whatever term one wants to apply to those who could never clear the horrors of war from their mind.

I connected particularly to those who talked about the “veneer of civilization.” We think we’re an advanced people, but you were put in situations that stripped you down to the animal/survival instincts that are at the core of probably every human being. And that core isn’t pretty, I’m sure. The sad part about combat for me would be to think about crossing a line where—out of a survival need—I would have become someone I may not have recognized or even liked. And I would wonder if I could have ever “backed up” across that line to return to the person I was. Maybe one can’t go back to who you were after such trauma. Maybe this is the ultimate cruelty of war.

I will close with a request. I would very much like to someday meet you, thank you in person, and visit over lunch or dinner. My wife and I could meet you in the Kansas City area. Whether or not that happens, please know how much respect and gratitude I have for what you did. You showed as much courage fighting in the war as you did fighting against it. For all you’ve done, I hold you in the highest regard.

Sincerely,

Mike Ransom

Two months later, I received the following reply from John along with inscribed copies of his books: Notes to the Man Who Shot Me: Vietnam War Poems and The Vietnam Years: 1000 Questions and Answers

Dear Mike,

First off allow me to apologize for taking so long to answer your letter. It just seems like I’m always playing “catch-up.” I’ve read your letter twice, and it sure is apparent we have had a lot of in-common experiences. We were lucky to be kids when we were. I’m very grateful for those years of innocence before we grew into the war.

Your dad sounded like a very good man who I wish I could have met. My father passed in 2000, my mom in 1987, and I miss them every day.

I’m enclosing a couple of books to show, hopefully, that my apology is sincere. The Vietnam Years came out back in 1986 and is long out of print. You may need to be careful with it as the binding is brittle.

Notes to the Man… is still selling well. I’ve been very lucky. In April of 2017 the book received the “Robert Gannon Award for Poetry” from the Marine Corps Heritage Foundation. The Commandant of our Corps presented me the award at the Marine Corps Museum in Quantico, VA. That was pretty “heady” stuff for an old corporal. Before you read this book, please read the Author’s Note first as I hope it will put everything in perspective.

Mike, I do hope you and your wife could get down here and go out to dinner with us. I’ll be proud to meet the two of you. Take care,

John Musgrave

Unfortunately, due the COVID epidemic and other reasons, John and I have not been able to meet for dinner. We have not forgotten, though, and we hope to do so in 2025.

Musgrave’s most recent book, The Education of Corporal John Musgrave: Vietnam and Its Aftermath, was published in 2021. I would highly recommend it.

Very interesting. I can relate to parts of that experience. Well written and in one of our visits Uncle Jim confided that the Korean War was much more difficult than WWII for him.