Here is my latest Writing Wit & Wisdom post that I welcome you to read, comment on, and share. And here’s a LINK to Ransom Notes where you can view the articles I’ve posted so far. Thank you!

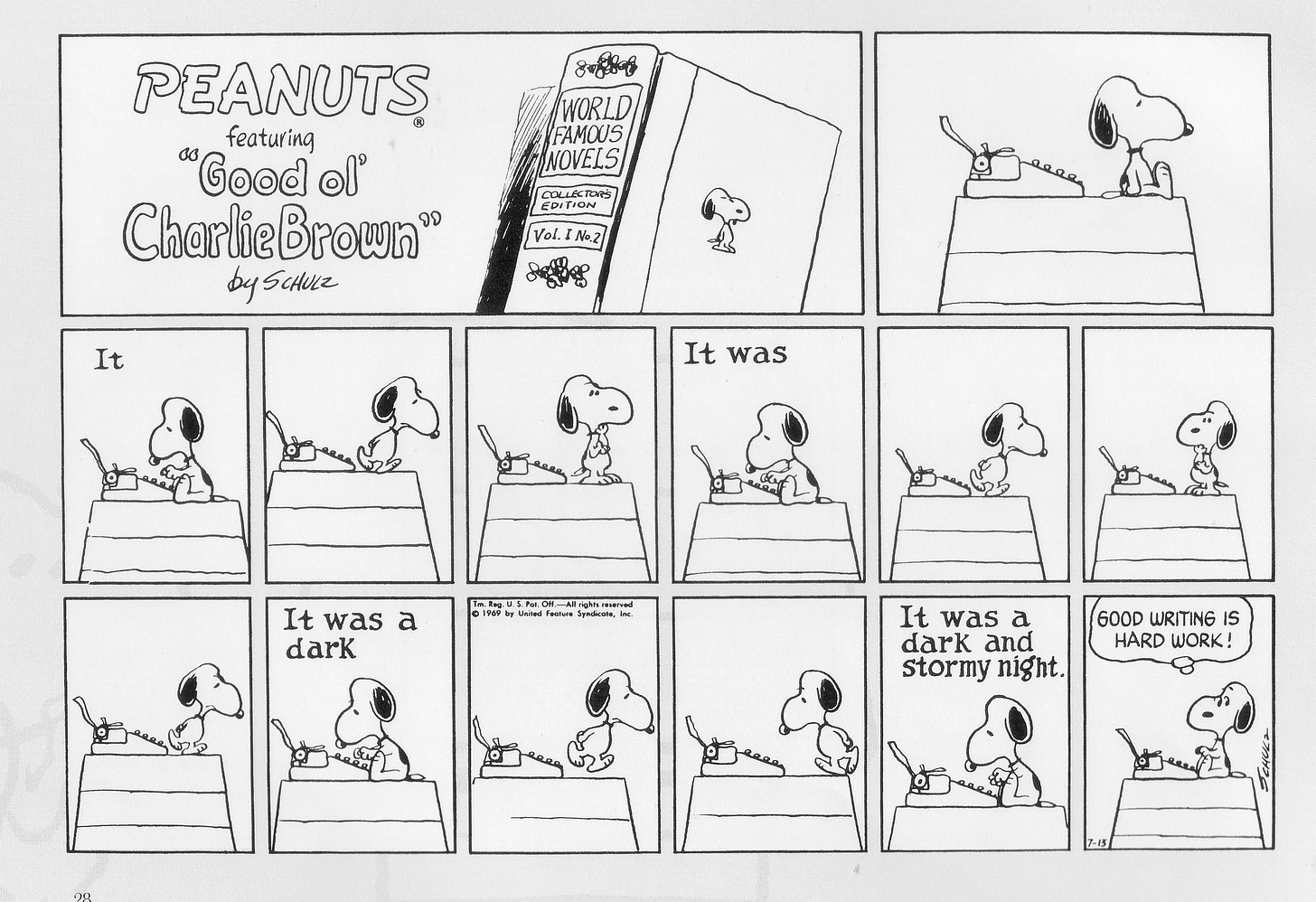

A Cartoon…

A Few Quotes…

If a book comes from the heart, it will continue to reach other hearts. ~Thomas Carlyle

Don't try to figure out what other people want to hear from you; figure out what you have to say. It's the one and only thing you have to offer. ~Barbara Kingsolver

In conversation you can use timing, a look, an inflection. But on the page all you have is commas, dashes, the amount of syllables in a word. When I write, I read everything out loud to get the right rhythm. ~Fran Lebowitz

Just because it happened to you doesn’t mean it is interesting. ~Dennis Hopper

A Heartbreaking Childhood

Robert Goolrick was an American writer whose first novel, The End of the World as We Know It: Scenes from a Life (2007) sold more than five million copies. He was born August 5, 1948, in Charlottsville, Virginia, and died in 2022.

His mother was a homemaker and his father a college professor, and he had two siblings. After losing his job as an advertising creative director and copywriter, Goolrick turned to memoir writing. His debut memoir highlighted “the excesses and failures of both the social underpinnings of the time and his parents’ inevitable alcohol-fueled decline, culminating in a devastating portrayal of the sexual abuse he suffered as a child.” He sought “something resembling peace” in his writing.

I have never felt sorrier for a person than I did for him after reading his book. I was born five days before him in 1948 in a small town in Iowa. My parents had little money but showed my sister and me an abundance of love…the opposite of what Robert experienced. How fortunate I was.

I am moved by his writing. The following passage from his memoir gives you a glimpse into his childhood:

It was all about perfection. My mother and father presented a perfect picture to the world, a happy, witty, and charming young couple who were madly in love, and did nothing but have fun.

My mother would get dressed to go out to an evening party, and she would come out into the central hall upstairs to brightly call goodnight to us. Our bedrooms opened into the hall, or at least mine did and my sister’s did, and my brother would come and sit on my bed to watch her say goodnight. Sometimes, most of the time, she would come in and we’d say our prayers, and sometimes she’d sing “Lavender Blue,” or “Oralee,” which had the same tune as “Love Me Tender,” and then she’d stand for a second in the upstairs hall, as my father stood impatiently at the bottom of the stairs.

As she stood there, my sister would call out from her bed, “Twirl, Mama, twirl,” and my mother would twirl, like a runway model, and we’d watch her skirts billow and her scarlet lips and her scarlet fingernails and the light brown hair my father once described as beige. It was her gift to us, her final goodnight kiss, and we loved her for it.

One summer night, when it was still twilight outside, my father called from the bottom of the stairs and she came out of her room in a sleeveless dress made of something blue, probably fake silk, that had a layer of chiffon over it. It had green and blue stripes on it, and the stripes were diagonal, going one way on the top and the other way on the bottom.

“Twirl, Mama, twirl,” my sister called out, and she did, twice around, and the stripes blurred, like a funfair whirligig that you can’t focus on once it starts moving. Then she blew us a kiss, and told us to say our prayers, and then her high heels clattered down the steps.

“Jesus Christ; my father said. “It’s after eight o’clock already,” and then they were gone.

This is the prayer we used to say, every night: “O Lord support us, all the day long, till the shadows lengthen and the evening comes and the busy world is hushed and our work is done and the fever of life is over; then in thy mercy grant us a safe lodging, a holy rest, and peace at the last. Amen.” We loved all those ands in a row. I still say it, every night, even when I feel I’ve lost my faith forever and God has already abandoned me a long time ago.

Ten minutes later, we heard her rush up the stairs, and she went into her closet in the hall and then into her bedroom and came out ten minutes later in another dress. I don’t remember the second dress and my sister didn’t call out and she didn’t twirl for us that time, just rushed off as though we weren’t there.

We were shocked. My sister and brother and I got out of our beds and crept into my mother and father’s room and there, lying on the bed, was the dress with the blue and green stripes. We looked at it. We looked at it closely because we didn’t understand what could possibly have happened. Then we saw it.

On the skirt, on the blue and green skirt with the diagonal stripes going the other way, there was a burn hole the size of a dime. You could see the turquoise underskirt through it. Obviously, she had been smoking in the car and dropped a cigarette ash on the dress and the ash had burned a small hole in the chiffon part. It wasn’t perfect anymore. She couldn’t wear it.

We went to sleep, and we never saw the dress again.

It was such a tiny, tiny thing. My mother smoked. She smoked in the car, her scarlet lipstick staining the filter. It was a gorgeous summer evening, and they were on their way to a lovely party, and they looked beautiful and my mother smoked in the car and burned a hole in the skirt of a blue and green dress. A tiny thing.

But it meant something had happened. Maybe they had a fight. They often did, terrible vitriolic fights. My brother would go to the top of the stairs and call out, “Please don’t fight, Mama and Daddy. Please don’t fight,” and my mother would come to the bottom of the stairs and look at her frightened son and say sweetly, “We’re not fighting. We’re just having a discussion, darling. Now go back to bed,” and he would, and they would go back to yelling at each other. Too many drinks, drinks after dinner and my mother’s bitterness at her own failures—she had wanted to be a poet— and my father’s failures— he had never finished his thesis. All this would come out and they would yell at each other.

But something had happened in the car. Something had happened to her beautiful dress, there had been some tiny, visible flaw created in the perfection of the whole, which couldn’t be allowed, some visible unhappiness, and we never understood it and we never asked because we never asked anything, and we never forgot it.

We loved our parents, our mother whom everybody adored and our handsome father whose hair turned snow white by the time he was forty. We loved them and we were afraid of them. We were afraid because we knew they were unhappy.

I used to think that there was something I could do to make it all right. I knew, somehow, that it was my fault, and I knew I could find the key to their unhappiness and open the door into a glorious world. I knew then we could all be happy and forgiven for the shame of being unhappy.

I used to concoct these ridiculous schemes. Every year around September, I began to dream that I could give them something for Christmas that would make a difference. I would build my father a boat. I would make my mother a diamond necklace. I would make detailed drawings in secret. With my twenty-five-dollar Christmas allowance, I would find some gem dealer who would be willing to sell me lesser diamonds and I would learn jewelry making and my mother would be amazed on Christmas morning and my father would have a sleek sailboat, and everything would be OK forever.

It never worked, and I always ended up getting my mother some costume jewelry brooch at Leggett’s that she never wore, and my father got handkerchiefs or a tie or a belt. No diamonds.

No boat. And I was always heartbroken at my failure. I knew a brooch or a belt wouldn’t make any difference.

When I was fourteen and had made some money in the summer mowing lawns and pulling weeds, I had my own checking account, and I sent away to Georg Jensen in New York for six crystal water goblets. My parents loved them, but it didn’t matter. I still have four of them.

When I was fifteen, I sent a check for twenty-five dollars to Andrew Wyeth and told him I knew it wasn’t much, but maybe he could send me a sketch he didn’t have any use for because my parents loved his work so much.

I waited in a panic for his reply, and it finally came, a nice note with a drawing of his house in Chadds Ford on it. He returned my check. My father showed the letter to everybody and then he had it laminated, destroying its value, and he had it framed in a cheap frame and hung it where everybody could see it and think what a funny and charming little fool I was.

When I was thirty, after my grandmother had died and the house my mother grew up in, the house we all grew up in, went into her estate, I bought it and gave it to my parents as a gift for their lifetime. My mother never even said thank you.

Nothing worked. They went on fighting in private and being charming in public, although some people began to see through the facade. One friend of theirs wrote in his photograph album, beneath a picture of the house I was later to buy, “When I first knew these people, I thought they were brilliant and beautiful and their house a magical place. Then I began to see them as ordinary and, finally, pathetic.” My brother saw it. He said later it was the exact thing that caused him to fall apart into his quiet madness some years later. I don’t know why anybody would write a thing like that in a photograph album.

She had burned a hole in her dress, and we had, for the first time, seen through the veil of perfection. That was all.

I wonder how many childhood memories have a similar longing for unrealized happiness. How difficult it seems to accept the foibles and failures of our parents.